Weekly Outlook

The light at the end of the tunnel?

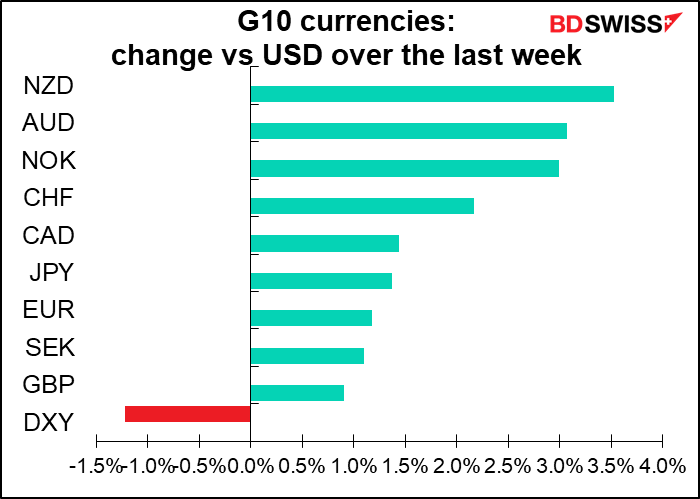

The big thing this past week was of course the surprising decline in inflation in the US. The consumer price index (CPI) was unchanged from the previous month and the producer price index (PPI) declined. The questions that the market wants to know from here are:

- Is this trend likely to continue?

- If so, how quickly will inflation come back to within the Fed’s target range? And

- Will other countries see the same sort of decline or is this change in direction unique to the US?

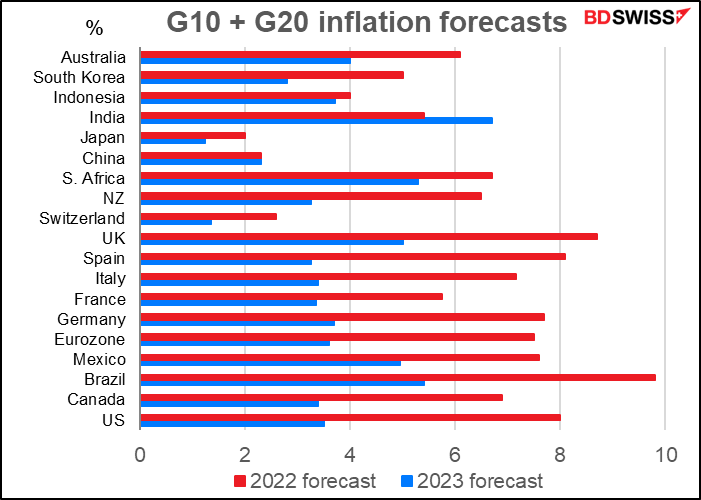

The market consensus forecast is indeed for inflation to fall this year.

And again next year.

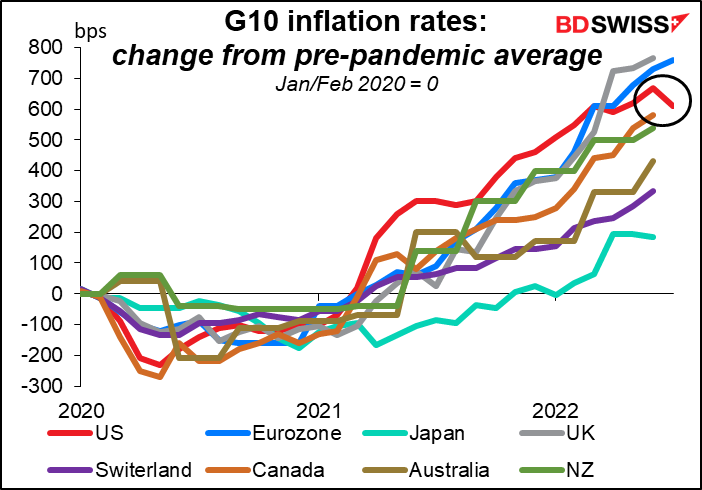

Inflation is somewhat synchronized around the world. One study from 2019 (Global Inflation Synchronization) found three major points:

First, inflation movements have become increasingly synchronized internationally over time: a common global factor has accounted for about 22 percent of variation in national inflation rates since 2001. Second, inflation synchronization has also become more broad-based: while it was previously much more pronounced among advanced economies than among emerging market and developing economies, it has become substantial in both groups over the past two decades. In addition, inflation synchronization has become significant across all inflation measures since 2001, whereas it was previously prominent only for inflation measures that included mostly tradable goods.

There are probably two main reasons why inflation is becoming increasingly synchronized around the world: one, the global trade in commodities, particularly oil, affects all countries, and two, the increasing interdependence of countries through trade and financial ties pushes business cycles in different countries towards synchronization. But as the-then Bank of England Gov. Mark Carney said in a paper delivered at the Fed’s 2015 Jackson Hole symposium (Inflation in a Globalized World), “Correlations of headline CPI largely reflect price level shocks such as those to oil. Core inflation rates exhibit much less comovement but rather vary with increasingly divergent underlying economic conditions.”

Each country has a different mix of problems that’s causing inflation to rise. In the US for example rents have been rising sharply. In Europe, the rise in gas and electricity prices is likely to keep inflation stubbornly high. Other countries may be more strongly affected by food inflation.

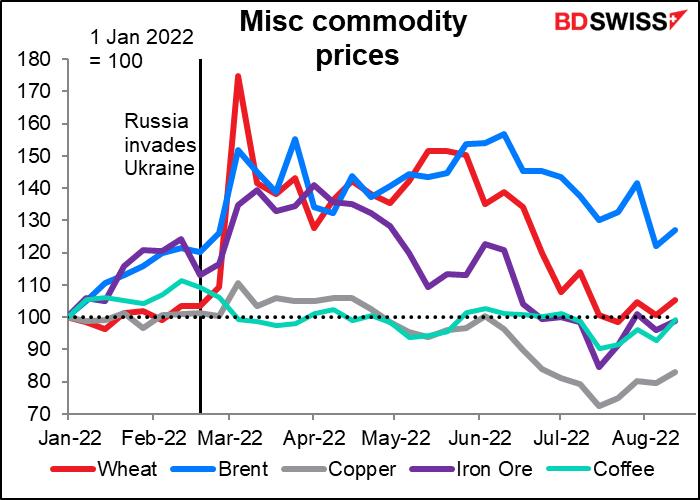

With prices of many commodities coming down now (natural gas, not shown, being a major exception) we’re likely to see headline inflation rates falling around the world, but the pace of decline in core inflation is likely to be slower and to vary more country-by-country. “In other words, domestic economic conditions—conditions affected by domestic monetary policy—still very much matter,” as Gov. Carney said. This means that there’s still plenty of room for “monetary policy divergence” trades as inflation slows.

Next week: UK, Canada, Japan inflation; US retail sales & FOMC minutes; RBNZ meeting

With everyone’s eyes on the global inflation picture, the big events next week are likely to be the Canada, UK, and Japan CPIs (Tue, Wed, and Friday, respectively). For the US, the big event will be the US retail sales figure and the release of the minutes of the July Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, both on Wednesday. And the Reserve Bank of New Zealand meets on Wednesday.

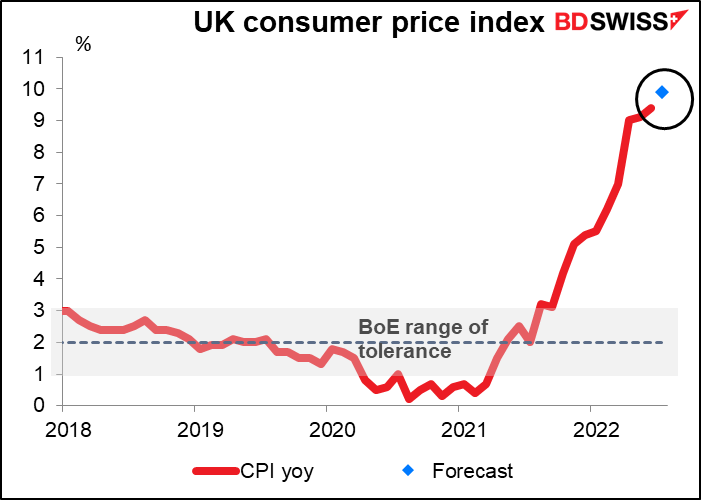

UK inflation is expected to rise further, to 9.9% yoy from 9.4%. This will surprise absolutely no one who has been paying even the slightest attention to British affairs. In the August Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of England said, “CPI inflation is expected to rise…from 9.4% in June to just over 13% in 2022 Q4, and to remain at very elevated levels throughout much of 2023, before falling to the 2% target two years ahead.” I would therefore expect a rise in inflation to have little impact on the pound.

And even when inflation starts to come down, people will be focusing on the rise in the official energy price cap, which limits the rates a supplier can charge for their default tariffs. The hikes to these price caps will add thousands of pounds to the average household’s energy bill when the next period begins in October. After that the cap will be adjusted quarterly, meaning if retail prices don’t start coming down then they’ll be passed on faster and faster to customers.

Britain will also announce its employment data (Tue).

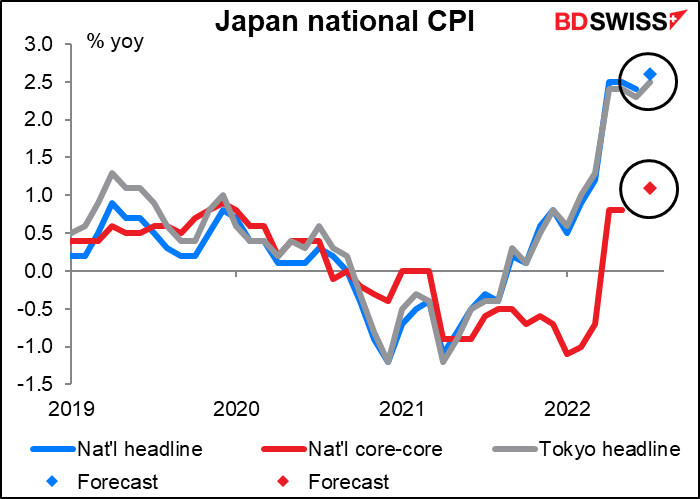

Japan, the global outlier in inflation, is forecast to see its national inflation rates inch higher. The headline rate is forecast to hit 2.6% yoy, a bit higher than the Tokyo inflation rate for the month (2.5% yoy). The headline inflation has been partly supported by higher food and fuel prices thanks to the weaker yen. That being said, price increases are spreading out to more and more components of the CPI, indicating a broader inflationary trend.

But note the forecast for “core-core” inflation. This is what goes by the name “core” inflation in other countries, i.e. excluding food and energy. This too is forecast to rise, but to what? 1.1% yoy. Even Switzerland, the apotheosis of low-inflation countries, has a core inflation rate of 2.0% yoy nowadays.

In the July Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices, the median policy committee forecast for the Japan-style core CPI (excluding fresh foods only) for FY2022 was revised up to +2.3%, but the forecasts for FY23 and FY24 remained below the Bank of Japan’s 2% price stability target. So far there are no indications that anyone on the Bank of Japan Policy Board is hankering to hike rates.

Nonetheless, Reuters reports that Japan PM Kishida is going to order his government to come up with ways to cushion the impact of rising energy & food prices on the long-suffering Japanese populace. “I will order additional, seamless steps to be taken focusing on energy and food prices, which make up most of the recent rise in inflation,” Kishida told reporters. With an inflation rate of 2.4% yoy (expected to rise to 2.6% in next week’s announcement), Japan hardly looks like a country troubled by high inflation.

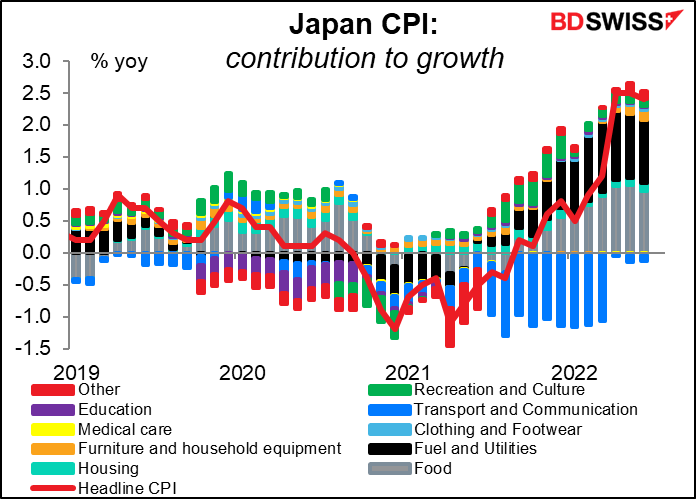

But PM Kishida is right that Japan’s inflation is concentrated in energy and food. In June, the latest month for which data is available, these two categories were responsible for 1.96 percentage points of the headline CPI’s 2.40% yoy rise. These are prices that the electorate is keenly aware of because they buy food and pay their electricity and gas bills regularly.

If the government takes targeted action against just these two categories, it could conceivably bring the headline inflation rate down below the 2% target without any change in monetary policy. I have no idea how they would do this, though. Some countries are cutting fuel taxes to relieve the burden, but food prices may be harder to deal with. Nonetheless, this would probably push headline inflation back below the Bank of Japan’s 2% target and alleviate any presure on the Bank of Japan to tighten policy – definitely a JPY-negative event.

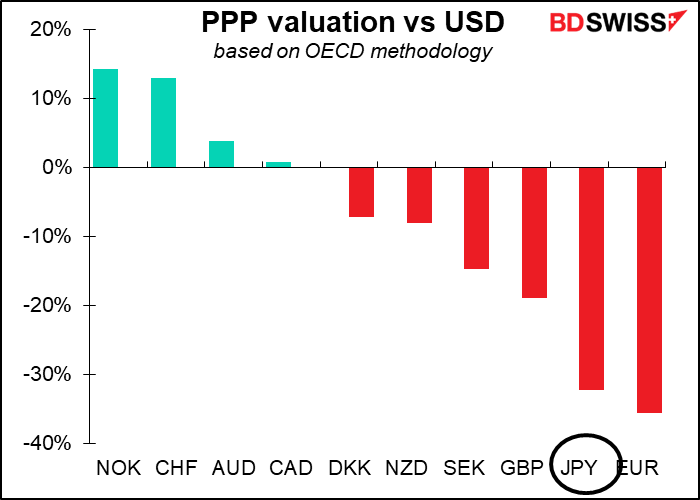

If on the other hand PM Kishida’s concern signals a change in Japan’s attitude toward inflation, it would be a major change in the foreign exchange market. The idea that Japanese interest rates will be anchored at zero indefinitely is one of the core convictions of the market, and with good reason. If the government starts to express concern about inflation and that convinction starts to change, then JPY – a significantly undervalued currency thanks to the Banko of Japan’s ultra-loose monetary policy – could come in for some rapid revaluation.

I would assume that until the “core-core” inflation rate is at or above 2% in Japan, there won’t be any voices on the Policy Board urging a rethink of their stance. This is why I think JPY is likely to remain weak for the foreseeable future.

Other Japan indicators worth watching during the week include tertiary sector index (Tue), and the trade balance and machinery orders (Wed).

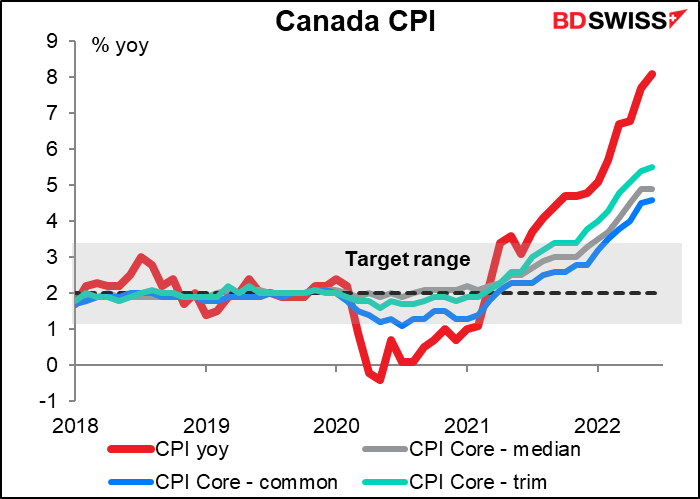

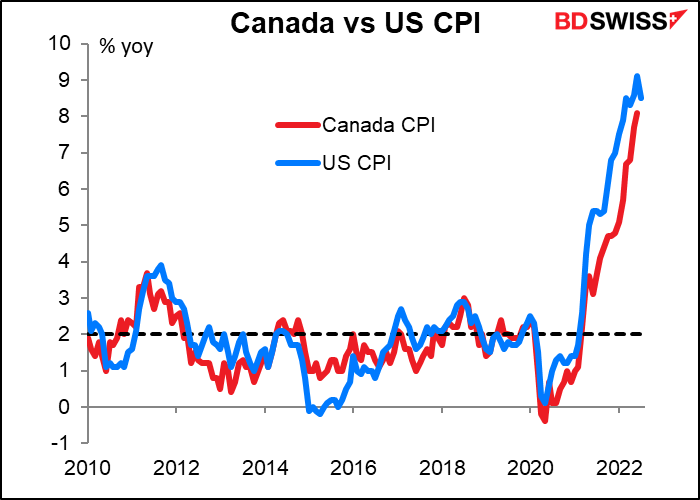

There are no forecasts for Canada’s CPI in the Bloomberg system yet.

However given the close correlation between Canada’s CPI and the US CPI, there’s a chance that we see a small downturn in the Canadian CPI this month. That would probably be negative for CAD if it were to occur.

Canada housing starts come out the same day as the CPI.

As for the US, there’s no more news on inflation due out this coming week. The focus will be on Wednesday, when US retail sales and the minutes of the July FOMC meeting are released.

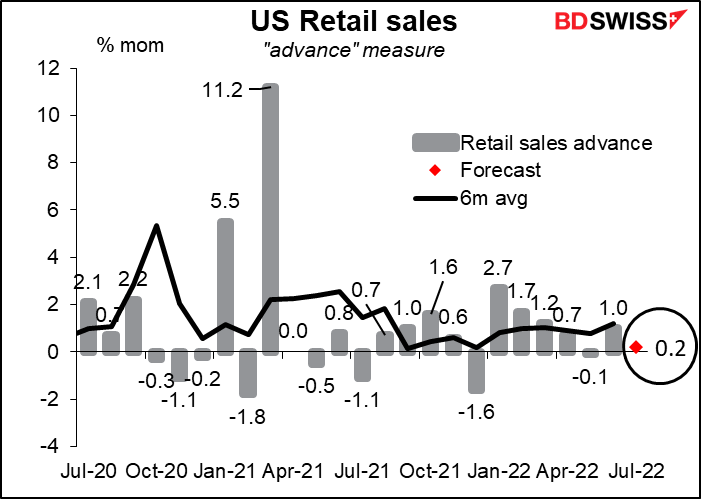

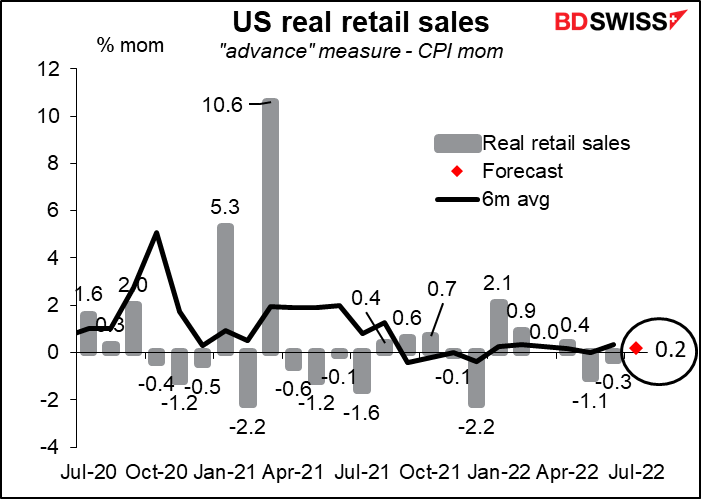

Retail sales have been trending upward recently but are forecast to rise substantially less in July. Still, with prices unchanged during the month, a 0.2% nominal increase in sales would be a real 0.2% increase, which is more than occurred during some of the other months when prices were rising rapidly.

If we subtract the month-on-month increase in the CPI from the retail sales figure, this is the picture we get. In this case, the forecast +0.2% mom increase looks pretty good. I would say that as long as retail sales are increasing, it shows that the US has still not fallen into recession. That’s positive for the dollar.

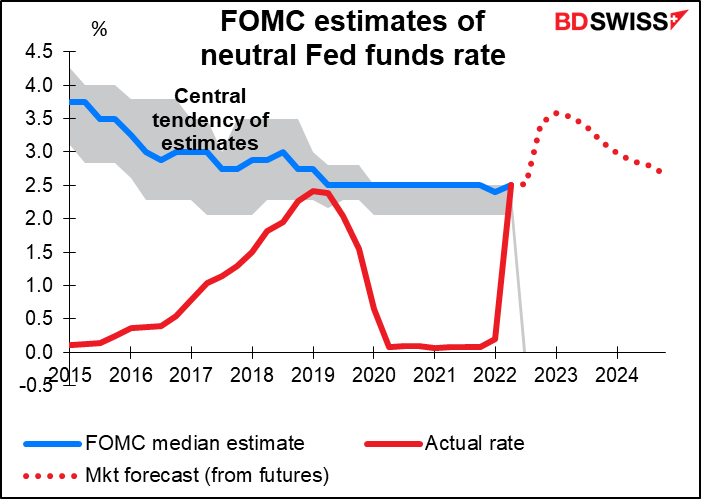

At the July 27th FOMC meeting, the Committee once again voted to raise rates by 75 bps. Market participants perusing the minutes will be asking: what did members think about September? What would get them to hike by 75 bps for a third consecutive time and what would get them to slow or even pause the pace of tightening? Are they content with the forecasts that they made in the Summary of Economic Projections in June? And what do they think now that they’ve hiked rates to what they consider to be “neutral”?

Other notable US indicators due out during the week include the Empire State and Philadelphia Fed indices (Mon & Thu, respectively), housing starts and industrial production (Tue), and the leading index (Thu).

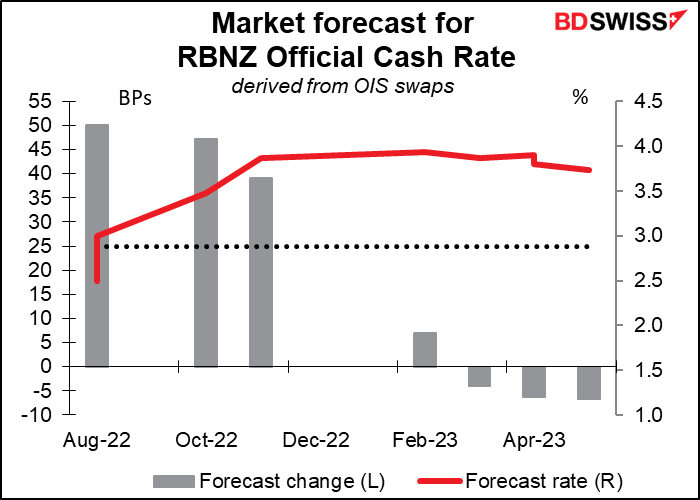

As for the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), it’s assumed that it’s coming to the end of its hiking cycle. The market looks for a 50 bps hike at this meeting, another 50 bps hike in October, 25 or 50 in November, and then basically that’s it.

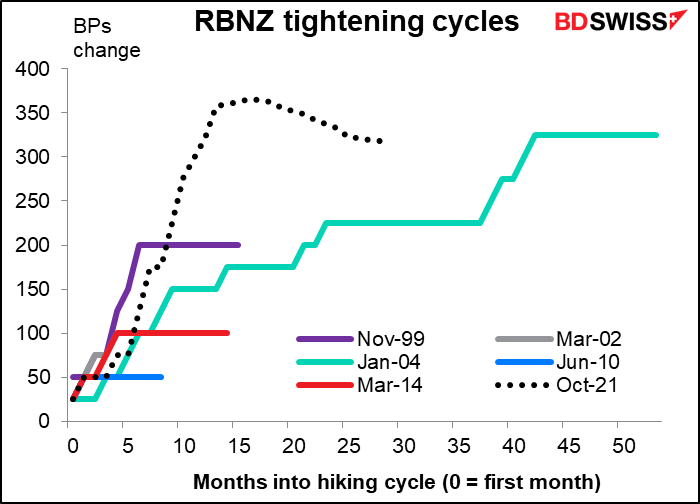

That would make this an extraordinarily steep hiking cycle. They hiked almost as much in the 2004/07 cycle, but that took 43 months. In this case, rates are forecast to have risen some 363 bs in 17 months.

As usual nowadays, the key is not necessarily what they do but rather what changes if any they make in their statement – whether they soften their rhetoric any. In this case, we should look for the word “at pace.” EG the last statement said that “The Committee agreed it remains appropriate to continue to tighten monetary conditions at pace to maintain price stability…” (emphasis added). However they removed the phrase from the forward guidance, which in June read, “The Committee agreed to continue to lift the OCR at pace to a level that will confidently bring consumer price inflation to within the target range.” (emphasis added) If they drop the phrase entirely, that might signa that after four consecutive hikes of 50 bps (assuming of course that they do hike by 50 bps this time) that they might slow to 25 bps next time. That would be negative for NZD if it occurs. On the other hand, if they keep the wording the same, then I don’t see the decision having much impact on the currency.

New Zealand’s trade data comes out on Friday.

Other countries

There’s not much coming out from the Eurozone, only the second estimate of 2Q GDP (Wed) and the final version of July CPI (Thu). GDP is usually not revised very much, just ±10 bps at most, so this is rarely a big event. Any major change in the CPI of course would be closely watched. We also get the ZEW survey (Tue), which is a sentiment indicator.

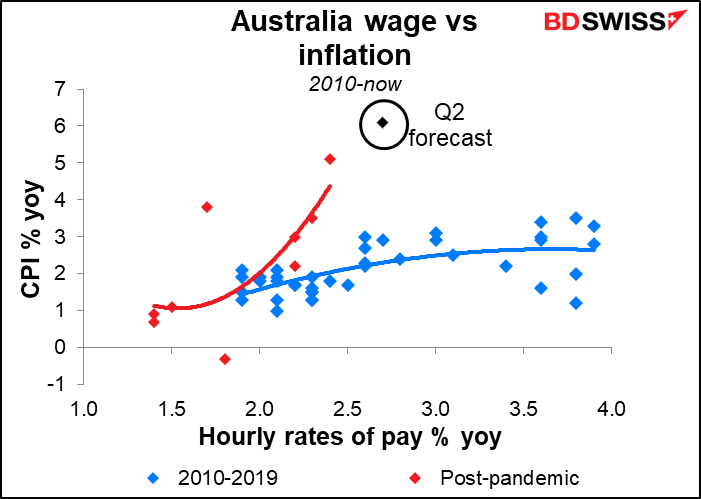

Australia releases its wage data (Wed) and employment (Thu). The wages data in particularly is a Very Big Deal as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) frequently pointed to the need for wages growth to get up to a level consistent with inflation in its 2%-3% target range. This data is available only quarterly and so can have a big impact when it comes out. Wages are forecast to have risen 2.7% yoy, which in the pre-pandemic world would’ve been compatible with inflation of around 2.8% yoy – quite firmly within the RBA’s 2% -3% target range. This should allow them to continue to normalize monetary policy, which is likely to be positive for AUD.

As for the employment data, the unemployment rate is already at a record low 3.5% and so this probably won’t have that much of an impact.